How Cape Town avoided “Day Zero”

Behind Cape Town’s most severe water shortage in 2017 and 2018 lies an inspiring story of how a compelling “Day Zero” campaign rallied people together to save water. Priya Reddy, Director of Communications, City of Cape Town, who led the campaign, shares lessons and enduring changes from the crisis.

| Writer |

|---|

| Serene Tng |

Share with us the circumstances leading to the need to launch the “Day Zero” campaign.

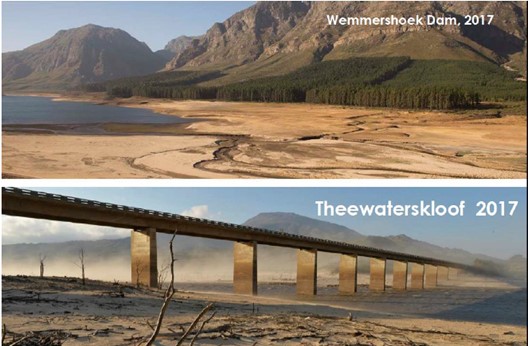

Priya: Even before this water shortage crisis, we already had some water use restriction for some years. Towards the end of 2016, we were told that things weren’t looking good in terms of the city’s water supply. We have not experienced rain for some time. In the background, our engineers and those from our water department were working hard to ensure that we had contingency plans to manage our water supply. By June 2017, we had already started asking people to reduce their water consumption to about 100 litres of water per person per day.

At the height of the water shortage crisis, the dams were down to just 9.8 per cent of their usable storage capacity. © City of Cape Town

At the height of the water shortage crisis, the dams were down to just 9.8 per cent of their usable storage capacity. © City of Cape Town

The turning point came when we realised that if we did not drastically reduce our water consumption, water will literally stop coming out from our taps.

Very often, communications staff like me are usually the last to know when a challenge like this unfolds. But as part of addressing the issue had to do with persuading people to reduce their water consumption, we became the first to know. We were able to develop a communications strategy and campaign right from the start with the budget and resource we needed.

Beyond the water saving measures we put in place, from repairing water leaks to placing water management devices in homes, communications played a vital role in encouraging individuals and businesses to significantly reduce their water consumption.

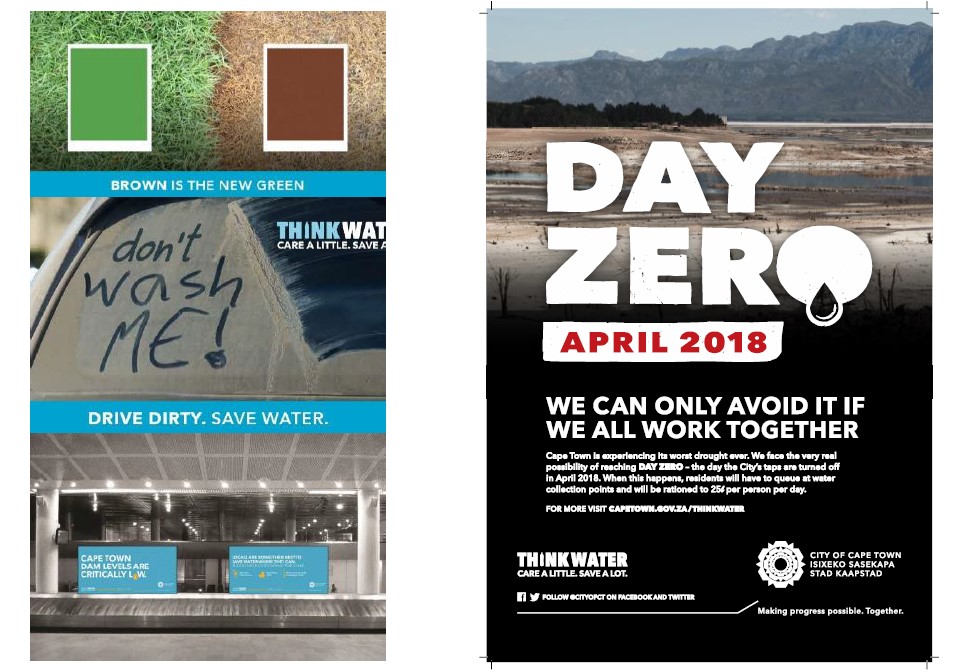

We implemented the “Day Zero” water campaign from January to December 2018 to rally people to significantly reduce their water consumption. By the time we launched the campaign, water consumption was restricted to 50 litres per person per day.

The Day Zero campaign used a variety of communication channels including Public Service Announcements, print and digital advertising, social media and community outreach. © City of Cape Town

The Day Zero campaign used a variety of communication channels including Public Service Announcements, print and digital advertising, social media and community outreach. © City of Cape Town

How did the term “Day Zero” as the campaign title came about?

Priya: The words, “Day Zero” was used by our water department colleagues in describing the situation. We had consulted with economists, academics and communications consultants on how best to communicate the situation effectively to people. We were advised that using “Day Zero” would be an effective communication term to use to make people realise how dire the water shortage was.

I was initially not comfortable with the use of the words. It implies that that would be a day that we would have no water at all. It wasn’t the case. We were not going to have no water at all. It was more that water may not come out of our individual taps, but you could still go to communal areas to get water. This scenario was already a very stark one for people to experience.

When we eventually launched the “Day Zero” campaign, it was meant to reflect the day that water stopped coming out of individual taps, not the day that you would have no water at all.

How did you use “Day Zero” in the campaign itself?

Priya: “Day Zero” was the worst-case scenario that we were all trying to avoid. It was a moving target in a way. In communications, we usually try to avoid painting the worst-case scenario that water may not come out of individual taps. However, we had to bring this across to show how serious the water shortage was. When bringing this across, we always included a caveat by explaining that it will happen if people did not significantly reduce their water consumption.

The power was in their hands to save water. This worst-case scenario we used in the campaign worked very well. It captured people’s imagination and galvanised everyone into action to do their part to save water.

What were some important lessons you learnt from implementing the “Day Zero” campaign?

Priya: One of the most important aspects of the campaign was to establish and build our credibility as a key source of information. When there is so much disinformation, fake news and with so many different players in the room, we worked hard to become the authoritative voice and source that people could trust and rely on for key information. During a crisis, we also learnt to find the right balance in sharing critical information quickly while ensuring that the information shared is robust and accurate.

Another thing that we learnt is you need to develop differentiated strategies and messaging to resonate with different groups of people. We have very diverse groups of people with different experiences with water. If you live in an informal settlement, you may get your water from communal water standpipes. On the other side of the city, some may have massive swimming pools and big gardens that need to be watered.

To determine the level of vulnerability across Cape Town, the city adopted a data-driven approach and developed its own Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and Economic Nodes Index (ENI).

To determine the level of vulnerability across Cape Town, the city adopted a data-driven approach and developed its own Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and Economic Nodes Index (ENI).

Initially, this stark differences in people’s access to water was a source of contention. But fortunately, everyone realised that this was a crisis that was going to hit all of us equally no matter who we were or where we lived. People eventually came together quite quickly to help one another.

A big part of the campaign was using local community influencers. Tell us more about this.

Priya: When you think about influencers, you usually think about those who have a huge following on social media. But for this campaign, we were more interested in working with local leaders and individuals who had a strong influence in local communities. This could be a person who was the key source of the neighbourhood gossip. It could be a school principal or the pastor of a church. The government is not always the best voice to influence and change people’s behaviour. We worked with such influencers to help us spread our water messages directly and this made an impact.

For example, religious leaders spoke about saving water in their sermons and even led the congregation to pray for the rain to come. We also worked with local provision ships to put up water-related posters.

You also explored some creative ways of communication.

Priya: We used drones to make water announcements to people. We also used sky banners, with banners coming out of planes to share water messages. In addition, we made water announcements at major sports games. We would go into shopping malls and teach people good water habits that would help reduce water consumption.

More than just asking people to save water, we actively showed people how to do so. For example, they could use a shower head that had a slower water flow. We advised people on how much water they should use for their daily essentials, from cooking, to washing dishes etc.

As part of the campaign, you published water consumption levels of key areas online. Why was this done?

Priya: Throughout the campaign, there were many occasions where we had to make tough decisions on whether we should do something more drastic or not. It was a dire situation that we had never experienced before. This was one of those difficult decisions. Given the serious situation, we felt we needed to do it.

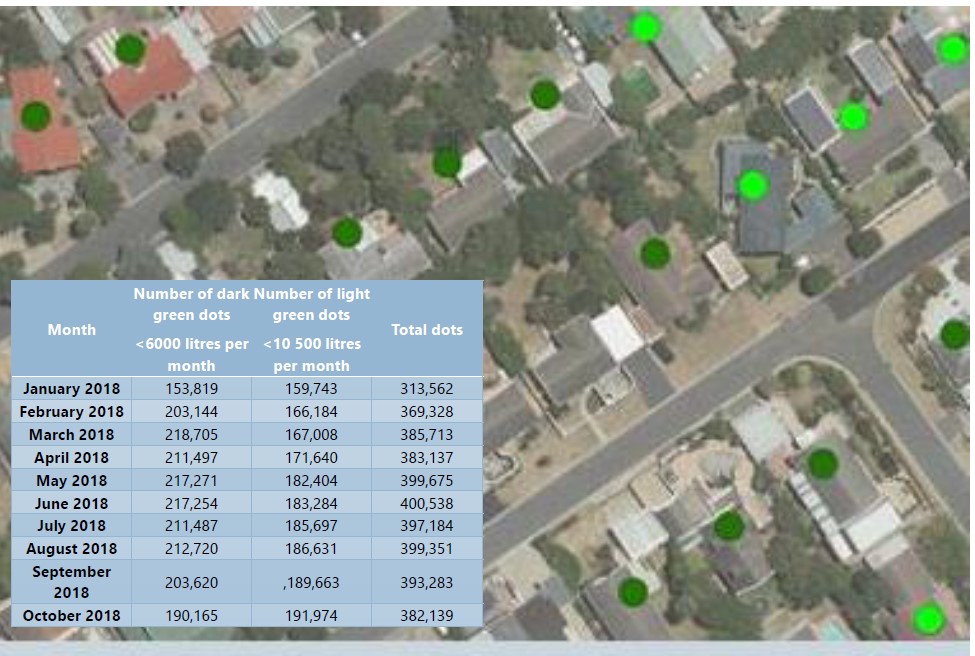

The Water Map allowed residents to see their water usage of their key neighbourhoods and areas. The map was colour coded, with green areas indicating households that were within the water restrictions and red areas indicating households that were exceeding the restrictions. © City of Cape Town

The Water Map allowed residents to see their water usage of their key neighbourhoods and areas. The map was colour coded, with green areas indicating households that were within the water restrictions and red areas indicating households that were exceeding the restrictions. © City of Cape Town

We published the water consumption levels of key areas on a green dot map. Names and addresses were not published. Individual houses were not identified but people could tell broadly which streets were using too much water. It became a friendly competition between the streets that encouraged people to save water. We took it a step further and created a competition between neighbourhoods. If one neighbourhood was doing well, we would put up street posters and banners to celebrate this.

What are some enduring changes about people’s attitudes towards water from the water shortage crisis?

Priya: People have learnt that having sufficient water supply is never guaranteed. Thus, we need to always be more responsible in how we use water every day. In fact, our current water consumption levels have continued to be lower than prior to the 2017 and 2018 water drought period. During the drought period, we had advised for people to shower with a bucket to save water. This habit has continued even after the water shortage crisis is over.

Cape Town is exploring to develop a permanent desalination plant in future to diversify its water supply strategy. © City of Cape Town

Cape Town is exploring to develop a permanent desalination plant in future to diversify its water supply strategy. © City of Cape Town

People are also more receptive to exploring more options to increase our water supply, for example, desalination. There is a greater acceptance of having to install water management devices in people’s homes. People are also checking on their water leaks more regularly.

In continuing to emphasis the value of water, we have deepened and differentiated our messaging and focus to educate people about what it takes to get water to come out of our taps. We share more about our water supply chain and the processes behind the scenes.

The crisis made us realise that we have the power to change things collectively and individually for the better. We can change our mindsets and narratives. It built a stronger spirit of resilience amongst our communities. It also prepared us for being able to better navigate and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. O